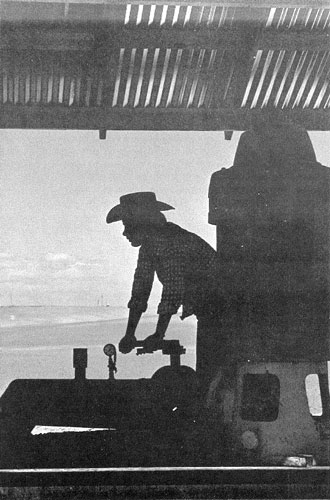

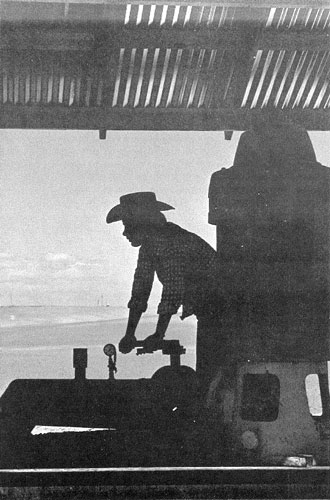

Smaller pumps create pressure for sprinklers

Smaller pumps create pressure for sprinklers

As had been the case in other areas of the Snake River Valley, potatoes were the primary crop planted on the new land. With sufficient fertilizer, the desert soil, which was rich in trace minerals, produced beautiful crops of Idaho Russets in the early years following reclamation. The unusually high return from a good crop of potatoes allowed a quick repayment of borrowed money on reclamation projects, making them an attractive investment. With increasing populations and the progressive marketing of the Idaho® potato industry, potato demand was increasing each year. Although some potato producing areas in the United States were suffering, the market seemed to absorb the increased production of the famous Idaho Russet without major problems.

Experience on the Dry Lake project indicated that the costs would be something in excess of $200 per acre. Early potato crops yielded 400 bags per acre with ease, so it did not take many years to pay off the huge investment required in projects of this kind. The new developers found help in their financing from a California-based irrigation company that wanted to develop a market for sprinkler pipe and from the Idaho First National Bank, long considered a promoter of agricultural expansion in the Gem State.

The Dry Lake development became an instant topic of conversation throughout the Idaho® potato industry. Many growers were aware of the fact that uncounted thousands of acres of fertile desert land lay on the plateaus to the south of the Snake River. With the engineering feasibility of high-lift projects established, development possibilities of new farmland seemed without limit. Enthusiastic support was received from the Idaho Power Company, whose newly created generating capacity in the Hells Canyon area found a market in the astronomical amounts of electrical energy that 1,500-horsepower pumps consumed during the growing season. The irrigation load was a natural for the Idaho Power Company since they were able to market their capacity in the winter months through the Northwest power pool when heating, lighting, and other domestic uses peaked demand.

No sooner was Dry Lake in production than Noble and his associates began looking further up the river for additional development possibilities. They found a large tract of desert land in the Sailor Creek area that had been used as a bombing and gunnery range during World War II but was no longer used by the United States Air Force and was available for desert entry filing. Forming a group of friends and associates that included farmer irrigation engineer J. T. Newcomb, the Sailor Creek project progressed quickly from concept through a feasibility study, and a block of claims was filed with the Bureau of Land Management. Sailor Creek presented an even more difficult engineering feat in that the water had to be lifted 725 feet from the Snake River.

Smaller pumps create pressure for sprinklers

Smaller pumps create pressure for sprinklers