In the middle of that second year, one of the first major actions to provide a uniform label that could be promoted for the Idaho potato industry was undertaken. The advertising commission suggested a uniform bag design with the purpose of identifying Idaho® potatoes. The regulations specified colored stripes on bags and packages denoting grade of potatoes (number ones, number twos, or combinations) and a new logotype design "Idaho" to be appropriately displayed.

In 1938, an experimental plant to produce alcohol from potatoes was being constructed in Idaho Falls under the direction of the University of Idaho, and the Advertising Commission was persuaded to contribute $3,000 to the project.

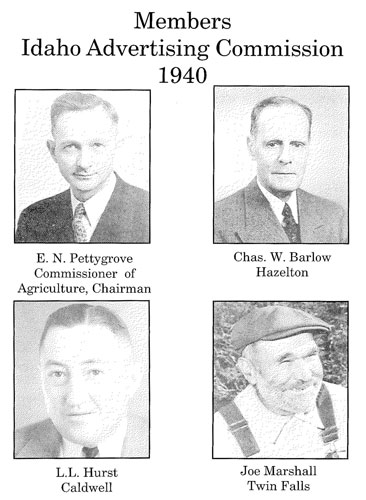

In spite of early successes, not everyone in the industry favored paying a tax to finance promotion of Idaho commodities and the Commission found itself involved in heated discussions and legal action concerning its right to levy an advertising tax on fruits and vegetables. A friendly lawsuit was undertaken which established the legality of the statute, but it was still necessary to change the law to quiet unrest in the industry. The 1939 Legislature eliminated apples and prunes from the program, changed the name to the Idaho Advertising Commission and cut the advertising tax on potatoes and onions from one cent to one-half cent per hundredweight. Also, seed potatoes were exempt from the tax.

Under the lower tax rate, advertising in newspapers was budgeted at $21,500 in 1940 and 1941, but dropped lower to $16,000 in 1942 and 1943, the early war years. As production increased in the industry, the next few years saw a steady increase and by 1947 the newspaper budget was $42,825.

At several meetings in 1947, the Commission discussed placing a seal on every bag of Idaho® potatoes to prevent receivers from "stripping" the bakers from the bags, refilling with small-sized and overly large potatoes and re-sewing the containers shut.

Although the amount of the tax was deducted from the payment to the grower by the first handler (shipper or processor), the shippers were responsible for payment to the Commission. Delinquent tax payments proved to be a constant problem from the very beginning of the program. During this era, about half of the potato harvesting was done by schoolchildren who were granted a special "spud vacation" to work in the fields. In 1947 they earned an estimated $800,000 for their work. But as the industry grew, the need for more farm laborers was apparent and the Commission's agencies did extensive advertising in the southwest section of the United States to encourage Mexican laborers to help in Idaho's fields.